What, my dear friends, could compel me to post after so long?

The Donald.

Doesn't he just shake up the political landscape? To quote the best Eddie Murphy stand up from the 1980s: I gotta story to tell.

So, I'm sitting at my daughter's volleyball practice and, as I am wont to do, I am grading papers. Out of the periphery of my vision I see a man turn to look at me. I raise my head and without any inviting inflection (no smile, no nod - I don't know this guy) he begins to just just talk:

"I'll tell you what. This country is gonna be MUCH better when Donald Trump is president."

Um. What? I must have stared at him blankly because he went on:

"And I'll tell you what. When Obama was elected, I KNEW this country was gonna fail and it did. You know why?"

Uh....

"Because he's not an American. And he don't even salute the troops!"

Uh....

"I gotta friend at Letterkenny and he says Obama don't even salute the troops and my friend served in Iraq and he knows that Obama don't even salute the troops and he's not a real American."

Uh...

"And I'll tell you what. I got nothing against women. I like women. My boss is a woman and she don't take no bullshit from no one and I like women. you know what I'm saying?"

Uh...

"So I don't got no problem with a woman president. Not Hillary -- she's shady as fuck. But a woman president? I got no problem with that. You know who would make a good woman president?"

Blank stare.

"Sarah Palin."

Okay. I know you think I'm making this up, and I have to admit -- when he threw down the Palin reference I started to look around for the hidden camera to see if Lonce Bailey was taping this for Facebook. I expected Ashton Kutcher to jump out and punk me. I started to think that he was a method actor from NYC who had come into town for a gig and got some extra scratch for messing with me. I didn't believe it was real for one moment because, honestly, I know no one who even thinks about Sarah Palin any more.

But then I realized that our media allows me to not know anyone who thinks about Palin any more. And therein lies the problem. We have stopped talking to each other and have started talking past one another. But I digress.

Most of my close friends who live in cities will think I am making this up for giggles -- but this guy is real as rain and he represents the 35% of the public who likes what Trump is saying. This is honest and raw and awful -- but it ain't no joke.

Remember how we used to chant: "We're here! We're queer! Get used it to and don't fuck with me!" Well guess what? Turn that on it's head and we have the Trump supporters.

Surprise!

My own personal Trump supporter (and apparent Palin aficionado) eventually ran out out steam (I will spare you the truly virulent racist stuff) and took a beat: "You a teacher? That's cool" wherein he went back to his iPhone and I sat in stunned silence. I hadn't ever spoken to him, nor had I had the chance to reply in any form, to correct the missteps or untruths and maybe that was for the best. He wouldn't have believed me anyway, and what's the point when talking to someone who had a

grammatical error on his tee shirt? (I took that photo before it all went down and sent it to my sister with a snort of laughter and cheer in my heart for typos.) Plus the tee shirt was right: I am thinking about him. Bless his heart.

The point here is not that Trump supporters are dumb, but rather they are angry a hell and it doesn't matter how many fact-checkers take him to task for just making shit up. We can dismiss the supporters, call Trump fascist, but in the end The Donald is here to stay and we might just have (cheers to YOU Niel Brasher!) a brokered convention.

He will not win a general (we all know that) but he will change the conversation and I think that change is for the worse. Not to be too blunt about it, but just watch the 2008 language at work: It was hope. It was lovely and it was positive. And it was right.

"Yes we can."

Where are we now, 7 years later? A nation plagued with hatred and anger and bigotry and a hint towards the kind of intolerance that I honestly thought we had moved beyond. As a human it makes me sad. But I listen to the 2008 video linked above and it gives me hope again -- because we are America. "And if we stand together we will begin the next great chapter in the American story with the three words that will bring hope: Yes we can."

We just need to get past this character. Trump. How dare he do this to us? He has a right - the Founders said so and I trust them. But they also created a system where he does not have to take over.

He's here. Get used to it. But don't stand for it.

Yes. We. Can.

The Invisible Primary

Saturday, December 12, 2015

Thursday, May 14, 2015

Once More, Unto the Breach Dear Friends

In the aftermath of the 2012 election, where GOP big shots from Karl Rove down to Mitt Romney sat stunned because they believed that the election was in the bag (and should have been in the bag), the GOP began a round of soul searching, as well as finger pointing (who can forget Mitt's double down comments crediting Obama's re-election to "gifts" to a variety of parasitical citizens)?

In the aftermath of this soul searching, the GOP produced a fairly interesting and revealing introspection about how the party would need to change if it wanted to win presidential elections, starting with the open-seat election in 2016. The result of this introspection is a 100 page document titled the "Growth and Opportunity Project". On page 69, the article focuses on the primaries, and especially the debates that took place among the potential nominees.

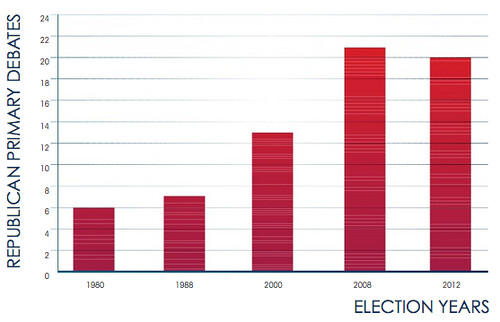

The authors note that in 1980, there were just six debates. In 2000 there were 13. But then in 2008 and 2012, the number of debates exploded, with 21 and 20 respectively. Furthermore, in 1980, the first debate did not take place until the Iowa Caucuses were about to begin, while in 2012 the first debate took place eight months before Iowa:

In addition to the large quantity of debates, there was the added problem of two debates held back to back within a 12 hour period--the first in the evening on Saturday January 7, 2012 and the second in the morning on Sunday, January 8, 2012.

The authors argue that it is time for the Party to get control over the timing, sponsorship, and candidate participation of GOP debates because currently the GOP brand, and candidates, are being hurt via a collusion of the liberal media and unelectable candidates who push for more, and not less, debates. They note:

Their recommendations for 2016:

The paper underscores a long standing tension between political parties, candidates, and the media when it comes to who or what matters during election time. Back in 1969, the McGovern-Fraser Commission changed the control over the selection of party nominees, removing it from the party leadership and handing it over to the rank and file voter in the 50 states and territories. As a result, who mattered in presidential elections shifted from Party-Candidate to Candidate-Media. In fact, we can lay a great deal of the blame at the feet of the Democrats for agreeing to implement the Commission reforms, because it brought with it the need for incredibly enormous sums of money and a near dependence upon political advertising (one going hand in hand with the other). Furthermore, it removed the party from having any influence over the choice of nominees, often getting stuck with the least desirable candidate. More recently, the political parties have been trying, with some success, to regain control over the selection of candidates and the direction of campaigns (see, for example, Groeling's When Parties Attack: Party Cohesion in the Media. NY: Cambridge University Press. 2010).

Jonathan Martin, writing in yesterday's New York Times, draws attention to the problems the GOP faces as it rushes headlong into the 2016 election cycle with a number of top shelf and bottom shelf candidates, versus the Democrats, who have Hillary Clinton and not much else (with all due respect to that loyal Bernie Sanders contingent). The article also illustrates a particular problem regarding who gets to decide who appears in those debates sanctioned by the GOP. From the lede:

At the moment, there does not seem to be a fair way to decide who appears and who does not. As Martin argues, relying on polling could preclude current or former GOP politicians from participating because they may not be well known to the public at large. What is especially ironic, or delicious, depending on your political views, is that public opinion polling is the weapon that the Democrats and Republicans use to keep third party candidates out of the presidential debates, and no one from either Party or from the Commission on Presidential Debates suggest any problems exist from using public opinion polling as a barrier to entry. The problem for the GOP is relying only on public opinion polling to decide who participates or not is likely to be the very thing that pushes candidates into appearing in non-sanctioned debates. And if some attend the non-sanctioned debates, you can bet most, if not all, will attend.

The GOP face the additional problem of optics in winnowing the field. From Martin:

So how does the GOP leadership see a way to resolve this problem? As Martin notes, for the first debate in August:

So pass the buck is your answer?

It may just be that the GOP leadership is looking at this in the wrong way. While I am sympathetic to the problem of over exposure--too many debates--as well as over simplification--too many people on the stage forces each person to boil down complex arguments into bite sized nuggets due to time constraints, the GOP should be asking themselves just what do debates in general accomplish? What impact do they really have on the eventual decisions that American voters make in November?

Martin seems to believe that debates do make a difference. He argues: "...as the 2012 primary demonstrated, televised debates can instantaneously reshape presidential races...".

He also suggests that candidates who do get excluded as a result of the criteria that the GOP, in conjunction with the media, develop will take their anger to

If you believe people like John Sides, these pre-primary and primary debates do not matter much in affecting the electoral chances of the eventual nominee. In fact, the benefit from these debates is two fold (at least):

First, it does act as a kind of training ground for the eventual nominees, who will only get three chances to debate one another in the general election (the list of potential debate sites is currently available at the Commission on Presidential Debates).

Second, these debates can save the party from making a very bad decision on a candidate who may be a media darling, but is nowhere near ready for prime time (think former Texas Governor Rick Perry).

It seems to me that the problem of superficiality, which some critics believe stems from too many candidates in the race, is less a result of the number of debates or the number of participants, and more the result of the media's role in the process, starting with sponsorship of the debates. Each one of the ten GOP debates is sponsored by a media organization--either cable or broadcast television. And if you recall the 2012 primary debates, the media coverage, coupled with the questions asked, were down right offensive to the intellect of the audience. Examples?

In the June 2011 debate that CNN sponsored, the moderator, John King, said this:

Or worse yet, who could forget the CNN "Tea Party" sponsored debate in September 2011, which had an introduction that was straight out of Monday Night Football or professional wrestling, or this from intellectual powerhouse Wolf Blitzer:

It will be something to watch as 2016 comes closer into view to see whether or not the Party, or the candidate, has real pull in the election cycle. But if the last two election cycles are any guide, having fewer debates is not likely to happen in 2016, or in any other presidential election cycle to come.

In the aftermath of this soul searching, the GOP produced a fairly interesting and revealing introspection about how the party would need to change if it wanted to win presidential elections, starting with the open-seat election in 2016. The result of this introspection is a 100 page document titled the "Growth and Opportunity Project". On page 69, the article focuses on the primaries, and especially the debates that took place among the potential nominees.

The authors note that in 1980, there were just six debates. In 2000 there were 13. But then in 2008 and 2012, the number of debates exploded, with 21 and 20 respectively. Furthermore, in 1980, the first debate did not take place until the Iowa Caucuses were about to begin, while in 2012 the first debate took place eight months before Iowa:

In addition to the large quantity of debates, there was the added problem of two debates held back to back within a 12 hour period--the first in the evening on Saturday January 7, 2012 and the second in the morning on Sunday, January 8, 2012.

The authors argue that it is time for the Party to get control over the timing, sponsorship, and candidate participation of GOP debates because currently the GOP brand, and candidates, are being hurt via a collusion of the liberal media and unelectable candidates who push for more, and not less, debates. They note:

The media will decide how many debates the party should have instead of the Party making the decision. In order to have a process that respects a candidate's time and one that helps the Party win (71).

Their recommendations for 2016:

- Hold between 10-12 debates beginning no earlier than September 2015 and ending somewhere around Super Tuesday in late February or early March.

- After the last round of debates, if there continues to be a competitive battle between two or more candidates (similar to 2008 for the Democrats), then it should be up to the candidates to decide if they want to accept or decline additional debates

- The RNC needs to get control of the scheduling process as soon as possible: by announcing the number of debates as well as when they will begin in late 2014 or early 2015, before the field of candidates has had a chance to get set. Further, the RNC should penalize any candidate or state party that defects from the schedule by attending non-sanctioned debates (or hosting non-sanctioned debates) by taking away delegates going into the GOP Convention in the summer of 2016, or more realistically, by barring from sponsored debates the participation of candidates who appear in non-sponsored debates.

The paper underscores a long standing tension between political parties, candidates, and the media when it comes to who or what matters during election time. Back in 1969, the McGovern-Fraser Commission changed the control over the selection of party nominees, removing it from the party leadership and handing it over to the rank and file voter in the 50 states and territories. As a result, who mattered in presidential elections shifted from Party-Candidate to Candidate-Media. In fact, we can lay a great deal of the blame at the feet of the Democrats for agreeing to implement the Commission reforms, because it brought with it the need for incredibly enormous sums of money and a near dependence upon political advertising (one going hand in hand with the other). Furthermore, it removed the party from having any influence over the choice of nominees, often getting stuck with the least desirable candidate. More recently, the political parties have been trying, with some success, to regain control over the selection of candidates and the direction of campaigns (see, for example, Groeling's When Parties Attack: Party Cohesion in the Media. NY: Cambridge University Press. 2010).

Jonathan Martin, writing in yesterday's New York Times, draws attention to the problems the GOP faces as it rushes headlong into the 2016 election cycle with a number of top shelf and bottom shelf candidates, versus the Democrats, who have Hillary Clinton and not much else (with all due respect to that loyal Bernie Sanders contingent). The article also illustrates a particular problem regarding who gets to decide who appears in those debates sanctioned by the GOP. From the lede:

Republican leaders, searching for a fair-minded but strategically wise way to conduct the presidential primary debates, are grappling with how to manage White House contenders in a sprawling field that mixes proven politicians with provocateurs and reflects an increasingly fractious party.

At the moment, there does not seem to be a fair way to decide who appears and who does not. As Martin argues, relying on polling could preclude current or former GOP politicians from participating because they may not be well known to the public at large. What is especially ironic, or delicious, depending on your political views, is that public opinion polling is the weapon that the Democrats and Republicans use to keep third party candidates out of the presidential debates, and no one from either Party or from the Commission on Presidential Debates suggest any problems exist from using public opinion polling as a barrier to entry. The problem for the GOP is relying only on public opinion polling to decide who participates or not is likely to be the very thing that pushes candidates into appearing in non-sanctioned debates. And if some attend the non-sanctioned debates, you can bet most, if not all, will attend.

The GOP face the additional problem of optics in winnowing the field. From Martin:

But if they decide to allow Fiorina and Carson to attend while cutting other candidates such as my State's Governor John Kasich, the GOP face the additional problem of appearing to embrace affirmative action.Many Republicans laboring to improve the party’s image recoil from the prospect that whatever debate-eligibility criteria are adopted could result in the barring of the only woman, Carly Fiorina, the former Hewlett-Packard chief executive, or Ben Carson, a retired neurosurgeon who is the only African-American candidate.

So how does the GOP leadership see a way to resolve this problem? As Martin notes, for the first debate in August:

One member of the national committee panel charged with overseeing the debates said its members had discussed ceding the decision entirely to Fox News.

So pass the buck is your answer?

It may just be that the GOP leadership is looking at this in the wrong way. While I am sympathetic to the problem of over exposure--too many debates--as well as over simplification--too many people on the stage forces each person to boil down complex arguments into bite sized nuggets due to time constraints, the GOP should be asking themselves just what do debates in general accomplish? What impact do they really have on the eventual decisions that American voters make in November?

Martin seems to believe that debates do make a difference. He argues: "...as the 2012 primary demonstrated, televised debates can instantaneously reshape presidential races...".

He also suggests that candidates who do get excluded as a result of the criteria that the GOP, in conjunction with the media, develop will take their anger to

...conservative websites and talk radio to foment anger at the so-called Republican establishment — an assault that could undermine the national committee’s hold on the debate process.

If you believe people like John Sides, these pre-primary and primary debates do not matter much in affecting the electoral chances of the eventual nominee. In fact, the benefit from these debates is two fold (at least):

First, it does act as a kind of training ground for the eventual nominees, who will only get three chances to debate one another in the general election (the list of potential debate sites is currently available at the Commission on Presidential Debates).

Second, these debates can save the party from making a very bad decision on a candidate who may be a media darling, but is nowhere near ready for prime time (think former Texas Governor Rick Perry).

It seems to me that the problem of superficiality, which some critics believe stems from too many candidates in the race, is less a result of the number of debates or the number of participants, and more the result of the media's role in the process, starting with sponsorship of the debates. Each one of the ten GOP debates is sponsored by a media organization--either cable or broadcast television. And if you recall the 2012 primary debates, the media coverage, coupled with the questions asked, were down right offensive to the intellect of the audience. Examples?

In the June 2011 debate that CNN sponsored, the moderator, John King, said this:

All right. I want to -- got to work in one more break before we go. We've got a lot more ground to cover. Believe it or not, our candidates -- we're running out of time here.

Into and out of every break we're having a little experiment called "This or That."

Governor Pawlenty, to you, Coke or Pepsi?

PAWLENTY: Coke.

Or worse yet, who could forget the CNN "Tea Party" sponsored debate in September 2011, which had an introduction that was straight out of Monday Night Football or professional wrestling, or this from intellectual powerhouse Wolf Blitzer:

“Tonight, eight candidates, one stage, one chance to take part in a groundbreaking debate. The Tea Party support and the Republican nomination, on the line right now.”And finally, regarding the worry about the power of the fringe to take to conservative media and to bring down the Party is giving to much credit to the fringe and to conservative media. As John Sides and Lynn Vavreck argue in The Gamble, one of the mistakes that Mitt Romney made in the primary back in 2012 was to over-estimate the power and the size of the Tea Party faction within the GOP, forcing him to take conservative stands when he did not need to. And political talk radio, once a force in American, and Republican, politics has disintegrated as a result of an aging audience and the continual fragmentation of our media into a million little pieces.

It will be something to watch as 2016 comes closer into view to see whether or not the Party, or the candidate, has real pull in the election cycle. But if the last two election cycles are any guide, having fewer debates is not likely to happen in 2016, or in any other presidential election cycle to come.

Friday, April 24, 2015

Zombie Myths: Invisible Primary Edition

Recently in the political science blogosphere there's been a venting on some of the enduring "zombie" myths. Despite the good work of several political scientists outreach towards journalists, and a warm reception to that outreach by many reporters, some of these myths just tend to stick around, the self-hair pulling and head bashing of the academy notwithstanding. Though I missed the tweet that started the avalanche over at Jon Bernstein's blog, and thus missed my chance to weigh in, I'll take the opportunity to throw out a few of my pet peeves in the coverage and perception of the invisible primary.

1. Money ≠ Success. Political scientists have known this for years. While I'm still not sure about money buying happiness (I'll volunteer to be in the experimental group on that test), we political scientists are quite certain that it cannot buy elections. Granted, much of what we know about money and electoral success comes from general elections, which are far more predictable than primary elections making campaigning and spending less important. Still, presidential primaries are national events, requiring a solid network of volunteers in state after state to be viable. While money can certainly buy some resources necessary for nation-wide network building, it still requires help that cannot be purchased. Support from office holders in the form of endorsements is key. Throw in the fact that it's these office holders that are actively seeking out good candidates in the invisible primary, we're left in a position where, last I checked, these aren't on the auction block.

2. Self-financed candidates are toast. I mean carbonized, burnt to a crisp toast. These folks are usually self-financed for a reason, they just don't have the networks necessary to win over party activists and their financial constituents. Even when they get a degree of funds from other donors, their lack of political experience and allies just leaves them at a systematic disadvantage. While this is something of an apples/oranges comparison, contrast the 2002 gubernatorial campaign of Mitt Romney with the 2010 campaigns of Carly Fiorina and Meg Whiman. Romney, who at that point had only an election loss or two as the sum total of his political career, was actively recruited invisible primary style by a handful of Massachusetts Republican activists. While the organizational ranks of Bay State Republicans is admittedly scant relative to the Democrats, they had a successful string of Republican gubernatorial runs. However, they were dissatisfied with the prospect of incumbent Jane Swift (who assumed office as a result of Paul Cellucci resigning to become ambassador to the Great White North) running in her own right, and unceremoniously dumped her for Romney. Fiorina and Whitman were classic cases of self-financed candidates that hit a ceiling, pushing the bounds of what money can buy you politically. At the state level it may in fact get you a nomination, but it won't get you too far when running for your party's nomination for the presidency. Just ask President Forbes.

3. Super-PACs and sugar daddies ain't everything either. While it's clear that super PACs are changing the dynamics of campaign funding, and they've yet to come into their own in terms of strategies and effectiveness, they're still an improper measurement of success in the invisible primary. Again, the invisible primary is an elite driven affair. Gregory Koger is spot on in his assessment that mega-donors a type of elite whose power is becoming more important at the expense of traditional party players through the ability to buoy poor candidates like Gingrich that would have been weeded out earlier in the process a few cycles ago. But at least for now, their donations are hardly determinative. And as his MoF colleague Richard Skinner points out, there's bound to be counter spending of super PACs and sugar daddies who are more party oriented to match the more candidate centered sugar daddies supporting the fringier personalities.

4. Ignore the polls. Political scientists as a class have been saying this for as long as polls have been taken at this stage of the election. As the invisible primary is largely, well, invisible, preferences of voters in the early stages have little predictive power at this stage. All the things that invisible primary success can bring a candidate (endorsements, party activist/network support, greater news coverage) aren't going to be apparent to the average voter until a few months ahead of Iowa, so there's no use asking them about their preferences that far out. Couple this with the fact that we have a ridiculously crowded Republican field at this moment, you're just not going to get much utility from asking voters their preferences right now. While they are readily available to busy journalists rushing to make a deadline (as opposed to where the real invisible primary action is), it's sour low-hanging fruit.

5. Especially those damned straw polls. Republican nominees Gramm, Bachmann, Robertson, Bauer, and Paul can tell you how prescient these things are, whether they're of CPAC or Iowa flavors. The events that surround them also tend to be terrible indicators of invisible primary success, since the crowds at these events are hardly representative of all the key invisible primary players. While they can be fun to watch, or indeed soul sucking experiences where we lose degrees of faith in democracy itself, they're not going to give you any real sense of who's going to come out on top in the nomination.

1. Money ≠ Success. Political scientists have known this for years. While I'm still not sure about money buying happiness (I'll volunteer to be in the experimental group on that test), we political scientists are quite certain that it cannot buy elections. Granted, much of what we know about money and electoral success comes from general elections, which are far more predictable than primary elections making campaigning and spending less important. Still, presidential primaries are national events, requiring a solid network of volunteers in state after state to be viable. While money can certainly buy some resources necessary for nation-wide network building, it still requires help that cannot be purchased. Support from office holders in the form of endorsements is key. Throw in the fact that it's these office holders that are actively seeking out good candidates in the invisible primary, we're left in a position where, last I checked, these aren't on the auction block.

2. Self-financed candidates are toast. I mean carbonized, burnt to a crisp toast. These folks are usually self-financed for a reason, they just don't have the networks necessary to win over party activists and their financial constituents. Even when they get a degree of funds from other donors, their lack of political experience and allies just leaves them at a systematic disadvantage. While this is something of an apples/oranges comparison, contrast the 2002 gubernatorial campaign of Mitt Romney with the 2010 campaigns of Carly Fiorina and Meg Whiman. Romney, who at that point had only an election loss or two as the sum total of his political career, was actively recruited invisible primary style by a handful of Massachusetts Republican activists. While the organizational ranks of Bay State Republicans is admittedly scant relative to the Democrats, they had a successful string of Republican gubernatorial runs. However, they were dissatisfied with the prospect of incumbent Jane Swift (who assumed office as a result of Paul Cellucci resigning to become ambassador to the Great White North) running in her own right, and unceremoniously dumped her for Romney. Fiorina and Whitman were classic cases of self-financed candidates that hit a ceiling, pushing the bounds of what money can buy you politically. At the state level it may in fact get you a nomination, but it won't get you too far when running for your party's nomination for the presidency. Just ask President Forbes.

3. Super-PACs and sugar daddies ain't everything either. While it's clear that super PACs are changing the dynamics of campaign funding, and they've yet to come into their own in terms of strategies and effectiveness, they're still an improper measurement of success in the invisible primary. Again, the invisible primary is an elite driven affair. Gregory Koger is spot on in his assessment that mega-donors a type of elite whose power is becoming more important at the expense of traditional party players through the ability to buoy poor candidates like Gingrich that would have been weeded out earlier in the process a few cycles ago. But at least for now, their donations are hardly determinative. And as his MoF colleague Richard Skinner points out, there's bound to be counter spending of super PACs and sugar daddies who are more party oriented to match the more candidate centered sugar daddies supporting the fringier personalities.

4. Ignore the polls. Political scientists as a class have been saying this for as long as polls have been taken at this stage of the election. As the invisible primary is largely, well, invisible, preferences of voters in the early stages have little predictive power at this stage. All the things that invisible primary success can bring a candidate (endorsements, party activist/network support, greater news coverage) aren't going to be apparent to the average voter until a few months ahead of Iowa, so there's no use asking them about their preferences that far out. Couple this with the fact that we have a ridiculously crowded Republican field at this moment, you're just not going to get much utility from asking voters their preferences right now. While they are readily available to busy journalists rushing to make a deadline (as opposed to where the real invisible primary action is), it's sour low-hanging fruit.

5. Especially those damned straw polls. Republican nominees Gramm, Bachmann, Robertson, Bauer, and Paul can tell you how prescient these things are, whether they're of CPAC or Iowa flavors. The events that surround them also tend to be terrible indicators of invisible primary success, since the crowds at these events are hardly representative of all the key invisible primary players. While they can be fun to watch, or indeed soul sucking experiences where we lose degrees of faith in democracy itself, they're not going to give you any real sense of who's going to come out on top in the nomination.

Thursday, March 5, 2015

50 Shades of CPAC

50 Shades of CPAC

We’re back! For a variety of personal and professional

reasons, the two primary contributors to this blog have been on something of a

hiatus since last summer. Speaking for myself, I’ve been as busy as I’ve ever

been in my professional life trying to make demonstrable progress on four

working papers under a 3-3 teaching load. There are times I truly envy my

friends in the private sector who only have to work 40-50 hours over a five day

work week…

In an attempt to hit the ground running, I’d thought I’d

elaborate a bit upon John Sides’ take on this go around of the annual CPAC

conference. In perhaps what is the best commentary I’ve seen on the event yet,

@monkeycageblog tweeted out this gem:

Let me preface the discussion with this: within my short

life as a political scientist, I’ve seen clear changes, good progress really,

in how the media covers the invisible primary. A decade or so ago, if the words

“invisible” and “primary” happened to collide together in the same sentence,

your average journalist, perhaps political scientist even, wouldn’t have had

the foggiest idea of what it was referring to. Compare that to the last couple

of presidential election cycles where reporters have routinely begun to refer

to the process and report on it in a much more informed fashion. This is

clearly a case where political science’s engagement with journalists has had a positive

impact on popular media coverage. Despite this wide recognition of the

importance of the invisible primary in steering the parties towards nominees on

the part of a growing number of journalists, the media tends to focus on

invisible primary events that are most conspicuous. And in this instance, it means

focusing in on the wrong place.

The problem with the CPAC conference is that this particular

piece of low hanging fruit is probably the least useful in getting a grasp on

which candidates are in doing best in the ongoing deliberations amongst policy

activists within the Republican party network. The history of success at CPAC

is far from perfect in predicting the eventual nomination. Let’s face it, the comments of a few fringe candidates make for

interesting news items, despite the fact that they test my faith in democracy in

general and more narrowly make me wonder how I ever had sympathies with this

particular crowd in years past (yes, it can be painful, hence the title). Couple

that with the fact that the straw poll gives a nice quantifiable capstone to

the event, you can see why journalists pay it a great deal of attention. However, CPAC is

at best a snapshot of the opinions of a few of the “fringier” factions within

the party. Libertarian-ish types, check; Populist Tea Party-ish types, check; a

good showing of Republican office holders, [crickets].

We know from experience, that the support of members of congress,

governors, and other elected office holders is absolutely key in winning the

invisible primary because of the organizational resources that they bring with

them and the cues they give to others in the party. Voters do indeed take heed to the opinions of the "elite". When the key party actors aren’t present in force for the

conversation taking place at CPAC, whatever visible cues we get from conference

will be a mighty incomplete picture of the party wide deliberation.

So props

Senator Rand Paul for his continued sweep of this series. And, a shout out to

Scott Walker for nearly pulling off a dark horse win. But when you’re a dark

horse behind Rand Paul, from a crowd that barely resembles the key constituents

of the Republican party network, neither of them, nor Republicans, nor the general public,

should be taking any of these results to the bank. I dare say we should stick with Prof. Sides, and look elsewhere for clues as to who's really cleaning up in the invisible primary.

Tuesday, June 17, 2014

Invisible Primary Ala Turca, Part Two

The invisible primary here in Turkey has taken a decisive turn in the last 24 hours. On Tuesday it was announced in a joint press conference held by CHP and MHP bosses Kemal Kilicdaroglu and Devlet Bahceli that they had made a "grand conciliation" to jointly nominate Ekmeleddin Ihsanoglu to run in the upcoming presidential election. While I certainly didn't expect them to take my advice and nominate Abdullah Gul, they've probably set themselves up for a duck in August's election (yes I do indeed use cricket terms). Though I don't know much about the person's background other than what's been reported today, I think this was about as bad of a decision as they could have made. Despite a sound reputation of intelligence, honesty, and a recent high profile spat with Erdogan, it's patent that he's a political neophyte and the two parties are making a very superficial ploy to name someone with a degree of Islamist street cred to take on Erdogan. Unless something big happens to bring Tayyip's reputation down in the next two months - and the man's survived the tapes where we hear him discussing how to hide a billion euros in cash of graft money with his son, so he's clearly made of Teflon - the effort will probably fall flat.

This isn't the first time these two parties attempted this kind of cooperation. In this spring's local elections the MHP and CHP coordinated by landing on a consensus candidate to take on the thoroughly corrupt Melih Gokcek in Ankara. Gokcek's mastery of patronage and populism has made him nearly invincible here. Despite the fact that he's clearly made hundreds of millions in graft and his city services are abysmal, he's developed an electoral base that no other individual or party can even begin to match. The consensus candidate in that contest was the mayor of Beypazari, Mansur Yavas (an outlying district in the Ankara municipality). Coincidentally, he floated his name a few weeks ago as an invisible primary candidate for the presidency. Until the 2014 election, he was a member of the neo-fascist MHP, though for the mayoral election he ran under the six arrows of the CHP banner. Pretty simple strategy they took: grab a fascist, slap a Kemalist label on him, hope they can bank on CHP brand loyalty in that corner of the electorate and that enough nationalist voters are willing to accept the compromise. It nearly worked. While there were widespread accusations of fraud, and an incident where a cat apparently caused a blackout disrupting the counting of ballots, the CHP lost by a slim margin. But still, the Ankara mayoral election gave both parties a glimmer of hope, yet showed just how touchy this triangulation on consensus candidates between these two parties can be.

That touchiness goes double for the presidential election. You honestly can't fault the opposition parties too much for this odd behavior and ultimate compromise. Despite them sharing a lot in terms of ideology (xenophobia, economic statism, hyper-nationalism, and a religious attachment to Ataturk), there's a lot working against effective cooperation between the MHP and CHP. Chief amongst those is the fact they hate each other in nearly absolute terms. There's literally been too much blood spilled between these two camps over the years, particularly in the time preceding the 1980 coup. That kind of hatred just doesn't evaporate in a few decades as their political identities were literally forged in that conflict and some rather important ethnic-religious dynamics that have been at play between these parties for years.

But more important than those factors, is that all of this is a rather weird learning process for the parties and electorate. There's a real paradox at play here: How can Turkey popularly select a constitutionally non-partisan office, whose historical purpose has been to protect the interests of the state elite from the people themselves? Compounding this paradox is the stark reality that Turkey has been wrestling with a changing of its state elite. While I clearly don't have the answer to this, I do know this is a highly consequential power play at a time of heightened social and political tensions.

The stakes are high as there is considerable ambiguity in the constitutional and legal structures defining presidential powers. Up until the presidency of Abdullah Gul, presidents were always representative of the Kemalist establishment and exercised their powers sparingly with deference to the bureaucratic-military elite. President Gul, despite the hoopla during his election has also exercised restraint, though his deference has been more towards the AKP and Erdogan. However, as several Turkish professors of politics and law have explained to me in my conversations over the past few weeks here in Ankara, there is great potential for presidential power to grow because throughout the constitution (and supporting law), the president is referred to as head of state, but doesn't have his powers neatly defined. Given these ambiguities, there's no doubt that Erdogan will push those potential powers beyond the pale resulting in de facto constitutional changes that will surely bring more conflict.

The sad part of the constitutional struggle is that there's widespread consensus that the present constitution, particularly the division of executive authority, is in desperate need of change. But there's absolutely no trust between the parties to even begin a productive conversation. Until there is some semblance of consensus, Turkey will have to settle for these strange fits and starts of constitutional evolution. As for the election of 2014, it is anyone's guess how the electorate will respond to the various candidates and how that power will be exercised by the eventual winner. For me, I just find it fascinating that despite the stark differences between our systems, there are some marked similarities in the invisible primaries in both nations. This undoubtedly speaks to the explanatory power the underlies our understanding of the invisible primary.

Labels:

Abdullah Gul,

CHP,

Ekmeleddin Ihsanoglu,

MHP,

Turkish Politics

Friday, May 30, 2014

Invisible Primary Ala Turca

Once again I am exercising my power as this blog’s macdaddy

to go off topic and discuss some pressing matters in Turkish politics. To say that Turkish politics is going through

an interesting time is clearly an understatement. Not only has Turkey recently embarked on a

disturbing reversion from solidly illiberal to near authoritarian governance,

they are wrestling with fundamental constitutional changes of selecting their president and the authority of the office. The most charitable

characterization of the care in which these changes have taken would be

reckless abandon. But we need to back up

for one moment to contextualize the changes in post-1980 environment.

The republic president is an office that carries mostly

ceremonial powers. While he is

technically the commander in chief of the armed forces and carries a veto power

over the parliament, military autonomy ensures that he exercises no real power

over military affairs and parliament can override a veto with procedures no

more difficult than a majority vote or two.

Formerly, the president of the Republic was chosen in a series of votes

taken in parliament. Generally, the high

numbers of parties in parliament and the deference (read sycophantic

capitulation) MPs would show to the military, ensured that the president would

have relatively broad support amongst MPs and be properly vetted by the TSK

(central military command). Until 2007,

this worked swimmingly for the TSK, as you’d expect it would given that they

wrote the constitution themselves. That

is until the rise of the AKP. As a

result of the 2002 election, the AKP had a solid majority in the parliament,

the first government in a generation that didn’t require a crazy quilt of

coalition for a confidence vote.

In 2007, Turkey stepped as close as it had to a military

coup as it had since 1997’s “post modern coup” where PM Erbakan resigned just

as tanks began to roll out of the barracks in Ankara’s suburb of Sincan. Just to give you sense of the military

posture in Ankara, it’s a surrounded by military bases, with tens of thousands

of troops (not just TSK bureaucrats) permanently stationed therein. A very visible reminder close to my old home

near Umitkoy, was a tank on permanent display next to the freeway with it’s

barrel pointed directly at the parliament building, a symbolic cue proudly

displayed with the subtlety of a sledgehammer (and yes, I checked the line on

Google Earth). But I digress. The constitutional crisis centered around PM

Erdogan’s nomination of then foreign minister Abdulah Gul. Erdogan had the audacity to appoint Gul

without vetting him through the military or the political opposition, as his

majority in parliament was sufficient to carry the vote without any other

support in the later rounds of balloting.

Despite following the military’s constitution to the letter, the

Kemalist establishment was furious, demanding that a new election be called

before the president be chosen. Rumor

has it, that a meeting of the national security council had been held

discussing the possibility of a coup (a right they reserved for themselves in

the constitution, ain’t that peachy) and that every force commander wanted to

pull the trigger, save the chairman Yasar Buyukanit, who ordered a “wait an

see” posture. Long story short, the coup

was avoided, a parliamentary election was held with the AKP taking a larger

share of the vote, and Abdullah Gul became president with as clear of a mandate

from electorate as possible and the tacit ascent of the MHP.

To avoid this sort of nonsense in the future, the AKP

forwarded a national referendum to amend the presidential selection system by

throwing the decision to popular vote.

Well the geniuses in the AKP elite didn’t really think out a few obvious

contingencies that even foreigners like me were asking. Along with the popular vote, the single 7

year term of president was shortened to 5 years, with the possibility of a

single reelection. But how would this

apply to President Gul? Must he abide by

the old term? Was he eligible to seek reelection? No one had answers until the constitutional

court chimed in, basically pulling a ruling out of the air. In fairness, they had to this time, as they had no

guidance whatsoever in the constitution, the amendment, or the law.

Another lingering question is the partisan

nature of the office. Formally, the

office is non-partisan. Though the nominations are made with the support

of a given number of MPs and then a series of parliamentary votes chose the

winner, once the person took office, they would eschew their former political ties, rise above petty squabbling, and focus on being a figure of unity in a highly fragmented political system. With a half dozen or so parties in any given parliament, a multi-party consensus (albeit militarily facilitated) had to be reached. Not so anymore with the decision made by the electorate and MPs free to nominate whomever they wish. While Gul has done this far better than most

had predicted in that he's not been as overtly partisan ad some had feared, the question remains for future holders of the office: Can a future president rise above the fray

now that they’re popularly elected in a ridiculously polarized system? Smart money would suggest no.

With Gul’s term coming to an end, and an election looming,

Turkey is again at a crossroads. Who

will be the candidates? What role are

the parties going to play? What other

changes are in store for the office?

On the question of who, this is still an open question. Erdogan is clearly in the running. Despite the office not carrying much power at

the moment, it still is an office of high prestige, and this schnook’s all

about showiness and prestige (the tackier and cheaper, the better). Also, he’s got designs on transforming the

constitutional powers of the office. Given his personality and nihilistic political ethic, he might not

wait for the formalities of constitutional amendment. While he and his supporters would tell you

he’s aiming for a French style semi-presidential system, the reality’s

certainly far darker. He’s already got

more relative power than the French President does. At best, we’d see a Russian model of weak institution with the locus of power being where the boss wants it, or possibly the Hugo Chavez model of hard

fisted, slash and burn kleptocracy. This

rightly sends shivers up and down the spines of everyone in the various

opposition parties, or those with any liberal democratic sensibilities. This puts the opposition parties in a

conundrum and the structural incentives of the new presidential selection

system is pushing them towards (wait for it…) a non-partisan invisible

primary! Well shit fire, who’d a thunk

that?

Normally the main parties of the opposition are farcical,

and I don’t think this is contained to the AKP era. Their irresponsibility is probably due in

large part to both the crazy

assed coalitions of the 90s and the absolute majoritarian nature of governance. Apologies

for the language, but that is the only way I can describe it. What else would you label a government

composed of conservative, fascist, and socialist parties (well, socialist for

Turkey) as they had in the wake of the 1999 elections? Other coalitions weren’t much prettier. How does an opposition even begin to oppose

such governments? Near as I can tell,

throw rocks at whatever it does, and hope you hit a soft spot on occasion

forcing a confidence vote or early election.

Not a particularly strong model for electorally responsible parties.

As to the absolute majoritarian bit, this is another curse

of Turkish illiberal democracy. In days

past, when coalitions were necessary for confidence votes, coalition partners

were hardly partners in any sense.

They’d simply divi up the ministries as per negotiated terms and

exercise exclusively within their domains, each party using the ministries’

budgets like ATMs and dolling out the positions to their peeps. Even communication was difficult between

ministries of different parties, as several foreign NGOs discovered in the relief

efforts of the 1999 earthquake. What

kept graft somewhat in check was the fact that not a single party controlled

the whole pie, and that there was a constant churning of governments preventing

any one party from controlling too much, for too long. The advantage of that natural check on

corruption came at the cost of good governance and stability. When politics is simply a zero-sum game to

control patronage, neither those in government or opposition are particularly

incented to create viable, programmatic platforms to present to the

voters. But again I digress.

In the current AKP era, opposition has been limited to two

parties: the CHP and the MHP (yes, there is a Kurdish party, though my heart is

with them, their marginalization is so severe that they can hardly be

considered a “normal” opposition party as they stand alone in this). Both parties are caught in a trap of trying

desperately to maintain their bases, which by necessity limits their

programmatic appeals to the broader electorate.

The CHP is a nationalist party that waves the Ataturk flag

most briskly of the lot. Despite the fact that it

quite literally isn’t the party

Ataturk founded (that party was closed with all the others in 1980), the “new CHP”

founder Deniz Baykal successfully claimed their label and substantial financial

assets in the early 1990s. An old expat

friend of mine from my Ankara days, referred to them as “sad old

Kemalists.” Though a bit of

generalization as there are some young folks in the party, it’s not that far

off psychologically. The base of the

party is largely the same today as it was throughout the first six or so

decades of the Republican era: people who are part of the military-bureaucratic

elite or the primary beneficiaries thereof.

Though Baykal is now out, brought down in a sex scandal a few years ago,

the current leadership follows the standard Turkish model of cadre parties

where power is highly centralized, intraparty democracy is non-existent, and

order is maintained through highly personalized networks within the party. The closest the CHP comes to a political

platform these days is a collective mourning of their lost privileges of old

and rather nondescript appeals to secularism that generally comes out as

rather course anti-religious rhetoric.

The MHP is in no better shape. The MHP is a neo-fascist party that picked up

on a thread of racial identity politics that emerged, gee wiz, in the 1930s and 40s. Turkish identity has always been rather

nebulous, but I think it’s safe to say that

most Turks take a rather benign definition of it, framed in Ataturk’s often

cited “Ne mutlu Türküm diyene.” Roughly translated: How happy is one who

calls oneself a Turk. As Ersin

Kalaygioglu puts it, if you say you’re a Turk, you’re a Turk! I can dig that. Not so the MHP. They’ve long exhibited the key traits of a

true fascist party: ultra-nationalism, wrapped up in a biologically determined

identity, a rejection of liberal individuality, voracious xenophobia, proclivity towards violence, glorification of

an imagined history, ideally reinforced by a heavy handed state. While their current leader Devlet Bahceli says reasonable sounding things from time to time

regarding the abuses of power by the AKP, never forget Bahceli came to power in

the party and maintains his power in the party by the naked use of force. Thankfully the electoral base of this party is

a bit smaller than the CHP’s, but it usually wins enough votes to break the ten

percent threshold making it a persistent player. Their politics are what you’d expect from a

fascist party – repugnant. While they’ve

gone through some window dressing in attempts to mainstream themselves for

broader appeal (with a degree of success), their core fascistic values remain intact. Straying too far from them has proved

risky in the past, and they’re unlikely to stray too much in the future

(they’ve made some consensus to Islamist elements in years past, which pushed

out some hard core identifiers, but that’s another story).

So, what now? Both of

these parties are undoubtedly going through an internal invisible primary right now to

forward some names to the Turkish people.

I don’t rightly care about that, since they’ll lose. As the invisible primary is all about

triangulating on viable candidates, which often means going with a number two

choice, here’s my advice to both the CHP and MHP: Go with Gul.

That’s right, I said it.

Go with Gul.

I say that not for their sakes, but the sake of Turkish democracy. Here’s why…

In the current political landscape both the opposition

parties are sure losers. I don’t care

who they nominate, the Turkish electorate will not go for another CHP hack moaning

about how hard it is to be a White Turk these days, or an MHP blowhard doing his

fascist thing, nor should they. Should both these parties nominate their

stereotypical selves, hello President Erdogan.

Gul has a genuine shot here. His

presidency has been unremarkable, which a

Turkish presidency ought to be.

While he’s taken heat for giving ascent to some repugnant AKP

legislation, his veto would have been

superfluous in the end as the parliament would just override it on majority

vote. Is he in my ideological camp? Of course not, none of these people are. But in democratic, electoral politics you play the cards you’re dealt.

Is such a marriage easy?

No. Hell no! Despite inhabiting a lot of similar

ideological space (statism, nationalism, xenophobia), it goes against the

virtual DNA of both the MHP and CHP to work together given their history. They are nearly as harsh of one another as

they are of the AKP. But if Bulent

Ecevit could hammer out a coalition deal with his DSP and the MHP, there’s

always that possibility (the DSP inhabited identical ideological

space as the CHP does, just with a different leader, did I mention parties were personalized in

Turkey?). Though the result of that government was

clear disaster, negotiating and governing with that coalition was a far taller

order than agreeing on a candidate for a largely ceremonial position. All of which is nothing to say of the

difficult pill to be swallowed by the CHP and MHP agreeing to endorse Gul individually. He’s the most prominent face of the AKP save

Erdogan himself, and his very nomination to president was the cause of the 2007

crisis. But recall, that it was the MHP that facilitated Gul's election in 2007, by attending a quorum call (a quorum that the constitutional court pulled out it's ass in its absurd annulment of the first attempt at Gul's election).

Though I hate false dichotomies for the sake of rhetorical

leverage, the way I see it, the opposition in Turkey has two options: nominate you own candidates to face Tayyip, get your ass handed to you in the election, and hold on for

whatever grand, looney, and destructive ideas he’s got in store for the office

and the nation. Or, go with Gul. You have a known quantity who’s probably

not going to recklessly blow holes in the constitutional order to immortalize

himself as the greatest statesman that ever ruled, anywhere, anytime. Are these good options? Not really, but again, play the cards you are dealt. Gul might be an ace in the hole.

Make no mistake, I’ve got clear baggage in this. I think the current constitution is rotten to

the core. Militaries suck at

constitution writing; period. Additionally, my disdain for all the main political parties ranges from strong to

absolute, as liberal democratic values aren’t embraced by any of them. But we must grasp at whatever shreds of

democracy we can to prevent Turkish democracy from backsliding into genuine

authoritarianism. For all its faults,

the present constitution is probably better than whatever Erdogan has in mind. And though Gul and I share little in

political values, he clearly doesn’t have the messianic hubris that Erdogan

displays. Should an Erdogan-Gul contest

be held, it’s anyone’s guess as to the result as I’ve seen no polling on it;

but I like those odds far better than an assured Erdogan win which the CHP and

MHP will hand deliver if they insist on nominating their own candidates for the

presidency.

Who knows, perhaps Erdogan getting spanked by Gul would signal the end of his career. If only we could be so lucky.

Friday, May 16, 2014

Don't Hate the Player, Hate the Game

Just a quick post here as I’m in Ankara trying to catch my

breath after the flurry of activity at semester’s end. Hopefully in a week’s time

I’ll be doing some real writing as I watch the Aegean Sea slowly pass by Didim…

Assuming Tayyip doesn’t block blogspot in the next few

minutes (I’m not kidding folks), I felt the need to expand on an interesting

post Seth Masket had today over at Mischiefs of Factions, where he presented a wonderful graph

courtesy of Poole, Rosenthal, McCarty, and Bonica. Masket rightly describes the situation

described here as a conundrum, we know the super-rich are underwriting a

greater and greater proportion of campaign costs and that as a class most

everyone of the big donors fit between

the party medians within congress, so it appears that they aren’t getting

everything that they pay for. Even the

“evil” David Koch inhabits this middle ground, though his brother Charles is

barely to right of the median point (clearly making him the evil brother). This makes intuitive sense. All these super-rich players are true intense

policy demanders; they have real policy goals that they don’t want to see

cocked up by extremist policy makers.

This echoes some research Ray La Raja and I did a couple years back in APR where we found that campaign

contributors aren’t the polarizing force in American politics that many assume

them to be. Using ANES data back to

1972, we concluded that politicians aren’t particularly responsive to

ideologically extreme donors as they are strategic in mobilizing ideologues in pursuit of financial resources towards

electoral goals.

Broadly speaking, political scientists are a rather skeptical

lot when it comes to campaign finance reform (at least for those of us who

study it closely). Especially

frustrating to us are the repeated calls towards reforms that we know would be

counter productive based on the empirical work we are intimately familiar

with. The campaign finance reform

quarters, quite frankly, are lousy with terrible ideas that would only serve to

exacerbate serious problems in American politics today. Exhibit A, polarization. Since our piece, more recent studies have shed

light on the role of mega donors, largely because of innovations in the

estimation of their ideal points. I’d go so far as to say that there is growing support that large donors are acting as a moderating force, a possibility that Ray and I looked for, but couldn't find given data limitations. We also suspected

that there is the potential for small donors to be a polarizing force should

some short term trends continue. Poole

et al’s graph here seems to give us some real empirical evidence to support

that idea.

One persistent call of the reform movement is for some

kind of structural support to encourage and/or subsidize small donors

through matching funds, clean election laws, and the like. While there is a nice, democratic, and

altruistic ring to the term "small donor," we should proceed with caution, as populistic

impulses rarely have positive outcomes when they are enacted into law. As of now, whatever polarizing effects small

donors have on our policy makers are probably being counter-balanced

by larger donors.

Amplifying the polarizing voices by juking the system in their favor

might only serve to drive the parties farther apart from one another. While I’m generally not an alarmist when it

comes to polarization, I’d say we’ve got enough of it right now as it is.

And yes, this has some relevance to the invisible primary. While fundraising is but a part of the game,

it is of real significance. It is also

one that is in constant flux due to the shifting legal sands that our finance

regime is based upon and the adaptability of the players. If there’s one constant in the history of

campaign finance, it’s unintended consequences.

Virtually every goal of reformers is thwarted in an election cycle or

two, and the “problems” they were trying to address wind up being more entrenched and acute. Should

legislation have the unintended consequences of enhancing the voices of the

most ideological extreme portions of the financial constituency, the

triangulation of party actors in the invisible primary will undoubtedly be affected.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)